Overcast autumn day. In the garden, in the alley under the old poplar, a table is served for tea. Samovar has an old nanny Marina. “Eat, father,” she offers tea to Dr. Astrov. “I don’t want something,” he answers.

Telegin appears, an impoverished landowner nicknamed Waffle, who lives on the estate on a position that has taken root: “The weather is charming, the birds are singing, we all live in peace and harmony - what else do we need?” But just the consent of the world is not in the estate. “It is not good in this house,” said Elena Andreevna, the wife of Professor Serebryakov, who had arrived at the estate twice.

These fragmentary remarks not outwardly addressed to each other enter into a dialogical dispute, echoing the meaning of the intense drama experienced by the characters in the play.

Earned for the ten years lived in the county, Astrov. “I don’t want anything, I don’t need anything, I love no one,” he complains to the nanny. Changed, broke Voynitsky. Previously, he, managing the estate, did not know a free minute. And now? “I <...> got worse because I was lazy, I’m not doing anything, and I just grumble like an old horseradish ...”

Voynitsky does not hide his envy of the retired professor, especially his success with women. Voynitsky’s mother, Maria Vasilievna, simply adores her son-in-law, the husband of her late daughter. Voynitsky despises Serebryakov’s scientific studies: “A man <...> reads and writes about art, understanding absolutely nothing in art”. Finally, he hates Serebryakov, although his hatred may seem quite biased: he fell in love with his beautiful wife. And Elena Andreevna reasonably reprimanded Voynitsky: "There is nothing to hate Alexander, he is the same as everyone."

Then Voinitsky exposes deeper and, as it seems to him, compelling reasons for his intolerant, implacable attitude towards the ex-professor - he considers himself cruelly deceived: “I adored this professor ... I worked for him like an ox ... I was proud of him and his science, I lived and breathed it! God, now? ... he is nothing! Soap bubble!"

Around Serebryakov, an atmosphere of intolerance, hatred, hostility is gathering. He annoys Astrov, and even his wife hardly tolerates him. Everyone somehow listened to the stated diagnosis of the disease that struck the heroes of the play, and all of their contemporaries: "... the world does not die from robbers, not from fires, but from hatred, hostility, from all these small squabbles." They, including Elena Andreevna herself, somehow forgot that Serebryakov is “the same as everyone” and, like everyone, can count on indulgence, on a merciful attitude towards himself, especially since he suffers from gout, suffers from insomnia, is afraid of death. “Really,” he asks his wife, “I have no right to a deceased old age, to people's attention to myself?” Yes, you have to be merciful, says Sonia, daughter of Serebryakova from her first marriage. But only the old nanny will hear this call and show genuine, sincere participation in Serebryakov: “What, father? Painfully? <...> Old ones that are small, I want someone to regret, but the old ones do not feel sorry for anyone. (Kisses Serebryakova on the shoulder.) Let's go, father, to bed ... Let's go, little light ... I’ll give you lime tea, I’ll warm your legs ... I’ll pray to God for you ... ”

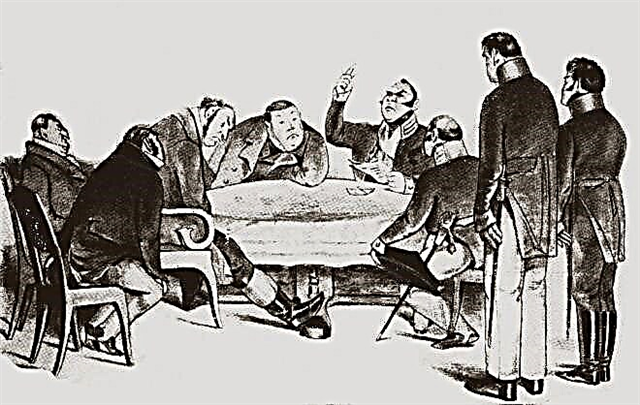

But one old nanny could not and could not, of course, defuse the oppressive atmosphere fraught with misfortune. The conflict knot is so tightly tied that a climax occurs. Serebryakov gathers everyone in the living room to propose for discussion a "measure" he had invented: to sell a low-income estate, to turn the proceeds into interest-bearing securities, which would make it possible to purchase a cottage in Finland.

Voynitsky is indignant: Serebryakov allows himself to dispose of the estate, which actually and legally belongs to Sonya; he did not think about the fate of Voinitsky, who had managed the estate for twenty years, receiving beggarly money; I didn’t even think about the fate of Maria Vasilievna, who was so devotedly devoted to the professor!

Outraged, furious, Voynitsky shoots Serebryakov, shoots twice and misses both times.

Frightened by mortal danger, only by chance passing him, Serebryakov decides to return to Kharkov. He leaves for his small estate named Astrov in order, as before, to treat the peasants, to take care of the garden and the forest nursery. Love affairs fade away. Elena Andreevna lacks the courage to respond to Astrov's passion for her. When parting, she, however, admits that she was carried away by the doctor, but “a little”. She hugs him "impetuously", but with an eye out. And Sonya is finally convinced that Astrov will not be able to fall in love with her, so ugly.

Life in the estate returns to square one. “We will live again, as it was, in the old way,” the nanny dreams. The conflict between Voynitsky and Serebryakov remains without consequences. “You will carefully receive what you received,” Professor Voynitsky reassures. “Everything will be as before.” And before the Astrov, Serebryakovs had time to depart, Sonya was rushing Voinitsky: “Well, Uncle Vanya, let's do something.” The lamp lights up, the ink bottle fills up, Sonia flips through the office book, Uncle Vanya writes one bill, the other: "February twenty twenty pounds of lean butter ..." The nurse sits down in a chair and knits, Maria Vasilievna plunges into reading another brochure ...

It would seem that the expectations of the old nanny have come true: everything has become the old way. But the play is built in such a way that it constantly - both in the big and the small - fools the expectations of both its heroes and readers. You are waiting, for example, music from Elena Andreevna, a graduate of the conservatory ("I want to play ... I haven’t played for a long time. I will play and cry ..."), and plays the Wafer guitar ... The characters are arranged like this, the move The plot events take such a direction, dialogs and remarks are soldered by such semantic, often subtext, roll calls that the traditional question “Who is to blame?” is pushed to the periphery, giving way to the question “What is to blame?”. It seems to Voynitsky that Serebryakov ruined his life. He hopes to start a “new life." But Astrov dispels this “exalting deception”: “Our position, yours and mine, is hopeless. <...> In the whole county there were only two decent, intelligent people: me and you. For some ten years, philistine life, contemptible life dragged on us; she poisoned our blood with her rotten fumes, and we became as vulgar as everyone. ”

At the end of the play, it is true that Voinitsky and Sonya dream of the future, but Sonya breathes hopeless sadness and a sense of an aimlessly lived life from the final monologue: “We, Uncle Vanya, will live, <...> we will patiently endure the trials that fate will send us; <...> we will humblely die, and there, beyond the grave, we will say that we suffered, that we cried, that we were bitter, and God will have pity on us. <...> We will hear the angels, we will see the whole sky in diamonds ... We will rest! (The watchman knocks. Telegin quietly plays up; Maria Vasilievna writes on the margins of a pamphlet; Marina knits a stocking.) We will rest! (The curtain slowly drops.) "

Thinking traps

Thinking traps